Muslims have been demonised in India. Now we are witnessing the violence that demonisation encourages.

-

![In Delhi, imaginary knives have now become real ones Women walk past charred vehicles following clashes over a new citizenship law in New Delhi, India, February 27, 2020. [REUTERS/Adnan Abidi]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2020/2/27/bd56d0b70e884e90b36d850fbc21ff0a_18.jpg)

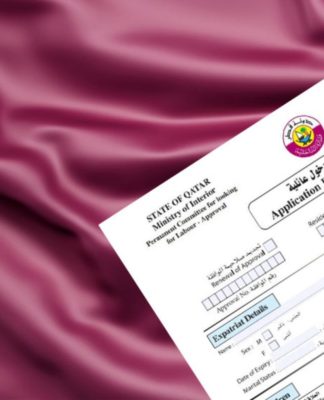

Women walk past charred vehicles following clashes over a new citizenship law in New Delhi, India, February 27, 2020. [REUTERS/Adnan Abidi] MORE ON INDIA

If the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in New Delhi and other Indian cities gave people here hope that we have the democratic, moral and intellectual legitimacy to question laws passed by the government, the anti-Muslim riots in the national capital have crushed that hope.

The CAA, which grants a fast-track to Indian citizenship for certain religious minorities but, crucially, not for Muslims, was seen by lawyers, activists and intellectuals, as much as by the Muslim community, as exclusionary and counter to the principle of equality enshrined in Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution of India. It was believed to be a precursor to the nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) that is currently being considered by the government.

The peaceful protests by the Muslim community, often led by women alongside political and social activists, writers, artists and students from all communities, marked an unprecedented moment in India’s postcolonial history.

They highlighted the intense proximity between people of different religious faiths in India. Protest sites like Shaheen Bagh, Seelampur and Jaffrabad are predominantly working-class Muslim neighbourhoods, where we saw people across class divides taking part in the protests. Not only did these protests offer important insights into the efficacy of nonviolent resistance, but they also produced new lessons in inter-faith harmony.

This democratic articulation of displeasure did not endear the protesters to the ruling establishment, however, nor to the supporters of Hindu nationalism.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s Kapil Mishra gave a speech threatening vigilante action against anti-CAA protesters once US President Donald Trump, who visited the country this week, had left. Mishra had made the speech in the presence of police personnel, which is, perhaps, why Justice S Muralidhar of the Delhi High Court expressed surprise when a senior police official claimed he had not heard it.

The inability of the Delhi police to handle the riots that have spread in the Muslim-dominated neighbourhoods of northeast Delhi is a disturbing but recurring sign of state complicity: it is difficult to imagine the audacity of a mob openly carrying out acts of arson and violence on the streets of the capital – the sense of impunity is palpable.

Threats of violence against anti-CAA protesters have literally come to pass. So far, 34 people have died in the riots and about 200 reported injured – 70 of them with gunshot wounds.

The numbers of dead and injured speak to the terror, damage to life and the extent of humiliation that Muslims have faced in the capital of India in the past four days.

Pro-Hindutva mobs have beaten up anyone who identifies as or looks Muslim, and destroyed Muslim property. The rioters, some of whom have been speaking anonymously to The Wire news website, sound full of hatred. They say they resent Muslims for protesting against the CAA. So it is all right if Muslims live in fear, but not all right if they assert their rights.

A flag featuring a Hindu religious symbol was placed on top of a vandalised mosque in Ashok Nagar, one of the northeastern suburbs of the city. Such acts of vandalism betray the most cynical form of religion, where religion is only what it violates, where belief is emptied of its spiritual roots, and the ethical constraints of faith are replaced by unfettered barbarism.

Babasaheb Ambedkar wrote in Untouchables or The Children of India’s Ghetto that denying moral agency to Dalits prevented Hindu society from developing a sense of “public” or “social conscience”.

It leads to a lack of moral guilt. Drawing an analogy from primitive societies, Ambedkar pointed out, just as “lawlessness against strangers is … lawful”, atrocities against people who are considered outside the territory of morality are not considered criminal.

Extending Ambedkar’s analogy, if a certain minority is painted as “outsider”, alien to the cultural imagination of the nation, then all secular sanctions that grant the minority equality before the law may be usurped by a territorial law of violence. Enough blood has flowed in the nation’s calendars, in 1984, 1992, 2002 and, now, 2020. India’s postcolonial history is marked by wounds.

I was coming back from the airport a week before the Delhi elections earlier this month, when the anti-CAA protests were in full swing. The propaganda machinery was already hard at work against Muslim protesters.

My Hindu taxi driver told me that Muslim neighbourhoods in Delhi were dangerous places, as people were getting knifed there. I asked him if he knew or had met anyone who had been knifed. No, he said, surprised that I had even asked such a question.

I told him that the nonexistent knife existed in his head and that people out there were planting knives in other people’s heads to create these rumours of violence and to enable real violence to take place. And now, Muslims are finally being harmed in their own neighbourhoods with these riots. Reality is the cruel antithesis of rumour.

It is a political tactic to spread rumours against minorities, so they are demonised in advance, and violence against them becomes acceptable. Majoritarian paranoia makes people fall for such divisive ploys, as the security they feel in their lives is prone to such baseless fears.

Only when there is nothing to lose can people be made to believe that there is everything to lose. The orchestration of hate works around fears like these, and leads to the majority losing its sanity, and its very semblance of morality.

The politics of violence takes advantage of this edgy condition, and that is when a nation diminishes itself.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.