02 May 2018 – 19:45

By Estelle Shirbon I Reuters

LONDON: As many as 270 women in England may have died prematurely of breast cancer because of an IT failure that led to 450,000 patients missing out on routine screening appointments.

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt apologised in parliament for the “serious failure,” which he said was the result of a mistake in a computer system’s algorithm dating back to 2009 but identified only in January this year. He ordered an independent review.

“Our current best estimate, which comes with caveats … is that there may be between 135 and 270 women who had their lives shortened as a result,” he said.

“Tragically there are likely to be some people in this group who would have been alive today if the failure had not happened.”

Britain’s state-funded National Health Service (NHS), which provides free healthcare to the entire population, is one of the country’s most popular institutions.

However, it is occasionally hit by failures and scandals which reverberate widely across society as almost everyone receives NHS care throughout their lives.

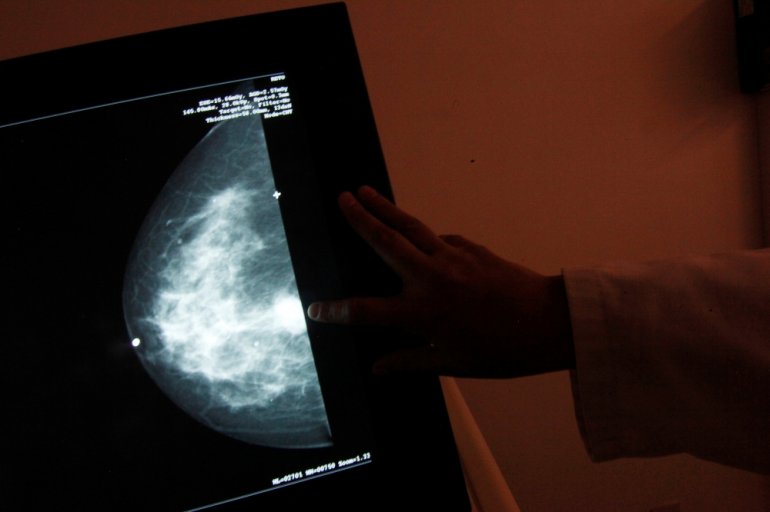

Under the routine NHS breast screening programme, women aged between 50 and 70 are invited for tests every three years. Around 2 million women are tested every year.

The IT error affected some 450,000 women aged between 68 and 71, who should have received their final invitation to a test under the routine programme but did not. Of those, around 150,000 have since died.

More than 300,000 of the remaining women, now aged 70 to 79, will be offered catch-up tests by the end of May, with all tests expected to be completed by the end of October.

“For them and others it is incredibly upsetting to know that you did not receive an invitation for screening at the correct time and totally devastating to hear you may have lost or be about to lose a loved one because of administrative incompetence,” said Hunt.

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in Britain, with more than 55,000 women diagnosed every year and nearly 1,000 dying of the disease every month, according to non-governmental organisation Breast cancer Now.

“It is beyond belief that this major mistake has been sustained for almost a decade and we need to know why this has been allowed to happen,” said Delyth Morgan, chief executive of Breast cancer Now.

“For those women who will have gone on to develop breast cancers that could have been picked up earlier through screening, this is a devastating error.”

CALLS FOR EXTRA CASH

The body representing radiologists said the catch-up tests would put even more strain on screening units that were already stretched to the limit due to staff shortages.

“Ultimately, we need funding for more training posts for radiologists to ensure the screening programme – and the NHS as a whole – has the vital imaging doctors it needs,” said Caroline Rubin, vice president for clinical radiology at The Royal College of Radiologists.

NHS funding and whether it is sufficient to meet the increasingly complex needs of the ageing population is a perennial topic of political debate in Britain. Staff shortages have been a concern for many years.

In the previous worst NHS patient care scandal, concerning poor practices at a small hospital in the English county of Staffordshire, an estimated 400 to 1,200 patients died between 2005 and 2009 as a result of inadequate care.

England’s breast screening failure follows unrelated news in Ireland last week that more than 200 cervical cancer test results should have resulted in earlier intervention.

The Irish government said 17 of the patients involved have since died, though it has not yet established the cause of death, and a further 1,500 women who developed cervical cancer over the last 10 years did not have their cases reviewed.

The government has ordered a statutory investigation into the scandal, which has dominated political debate and shaken confidence in the Irish health service.

(Reporting by Alistair Smout and Estelle Shirbon in London, Padraic Halpin in Dublin; editing by Stephen Addison and Richard Balmforth)