The UN has made it compulsory on European countries to arrest anyone intending or even voicing intent to travel to Syria and Iraq. So anyone trying to exercise freedom of speech and support the mujahideen right to fight in defence of their life’s wealth is a terrorist.”

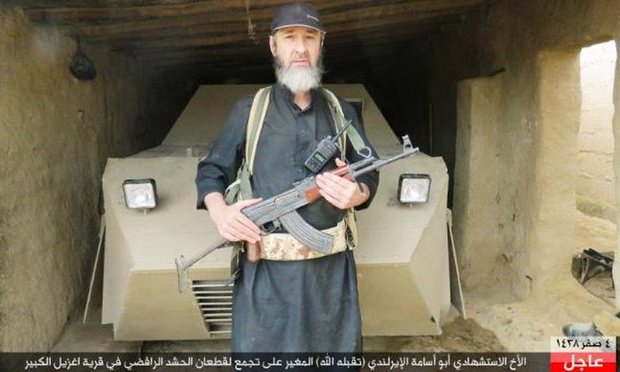

This was how my correspondence with Khalid Kelly, born Terence Edward, began. It was late-September 2014, 26 months before his death in Mosul on 4 November. He had driven a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device into the village of Ghzayel al-Kabir, targeting the Shia popular mobilisation unit. The news was somehow both unsurprising and completely shocking.

In the Irish press, he had always been a reprehensible clown: that lunatic who threatened to assassinate Barack Obama on the 2011 presidential visit. He would spout offensive diatribes, anti-western in their content, though he seemed content to live between Dublin and London.

My interest in speaking with him occurred only after the beheadings of the aid worker David Haines and journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff. He appeared on Chris Barry’s FM104 radio show, insisting the militants had “no other choice” but to execute these men and, as a result, the inflammatory statement prompted police to request the interview tapes.

While this investigation was underway, I contacted the station to see if I could acquire a means of contacting him. A producer, however, said it was hopeless. His phone was no longer in use. “He’s gone underground. Maybe check his Twitter?” And, oddly enough, his attention was easy to capture. Messaging him, with a request to discuss free speech, within minutes he came up on a private chat.

“Go ahead. You’re welcome.”

We swapped emails. He wrote: “The situation right now is not easy for anyone wishing to speak the truth.”

Quickly, it became clear he would not entertain questions. Rather he just wrote at me, explaining how his duty to “educate” was undermined because free-speech seemed “relative to whether you’re Muslim or not”.

“You’re innocent until proven Muslim”, was how he characterised his treatment, recalling a specific incident from 2010, months after his return from Swat Valley, Pakistan, where he trained with the Taliban.

“My flat got raided by anti-terrorist police. I was beaten badly. A friend of mine had a bag placed over his head. They beat him so badly they burst his eardrum.” That was commonplace, he said, claiming there was no justification behind such aggression.

Emphasising how incompatible his duty was with Ireland, and scornful of how the Shia community “agrees with most western views”, he simply refused to accept the hypocrisy of having only left Ireland once in the 16 years, since he converted to Islam while incarcerated in a Saudi prison for brewing alcohol.

Ignorant, but friendly, there was scarcely anything intimidating about him, save his stated objective to control “all Muslim land and from there liberate the whole world from the control of Jews [and] USA”. Departing with a kindly “take care”, for a week he ducked all emails, his eventual reason being “dental extraction”. Once the article was published, however, he was back on to me with a “not too bad”.

Yet, as the months went by, and he was said to leave Ireland again, his manner changed until I was essentially talking with an outright belligerent preacher, this peaked after the Charlie Hebdo shootings took place. “Alhamdulillah”, he wrote “We have now re-established Khalifa. The world has not seen anything like this in recent history. Now things will change.”

Condescending once the free-speech debate had flipped, he mocked the western concept as a mere “freedom to insult”. There was only one law, and now Europe had to experience that dealt in Iraq and Syria daily. “The prophet Muhammad said Islam will have authority in the east and the west. Islam will be dominant everywhere. Justice will prevail.”

Predicting an “all-out war”, he saw “no answer to violence [besides] violence”, and although this online sermon was spoken with utter certainty, nonetheless, he signed off by adding: “Will not say more until all facts have become clear. Inshallah for now, take care, embrace Islam.” His fiery Twitter activity clogged up my feed, but we fell out of contact.

At some point thereafter, he returned to Ireland, with his activity monitored by the Garda counter-terrorism international unit. Moving to Ardagh, County Longford, his house was raided and €30,000 was uncovered, with speculation that this was to facilitate his eventual journey into Iraq via Turkey.

The next I heard of him was that he was dead and going by his Twitter handle, Abu Usama, and with this Ireland had a serious question to consider. Kelly was but one of an estimated 30 Irish nationals who have travelled into the war zone, yet he was the only vocal radical.

This news gives greater urgency to the persistent warnings of many Irish imams, who insist a breakdown in communication has alienated many young Muslims in their communities. In August of 2015, Shaykh Umar al-Qadri, chairman of the Irish Muslim Peace and Integration Council, recalled an incident in which he was threatened by Dublin men who claimed: “We are Isis”, while estimating about 100 sympathisers currently live in Ireland.

Whether alienated by US military use of Shannon airport as a stopover point for refuelling, or the growth of anti-Islamic political groups such as Identity Ireland, or Pegida Ireland, the Irish are part of the “Coalition of Devils”. It could be argued that this is an honourable title. Certainly, it is not shameful. Yet, such a classification cannot be treated lightly.

The gradual collapse of Isis in Iraq and Syria, Irish security experts suggest, may result in fighters returning home. If that is the case, then even if the national threat is moderate, our desire for peace ought not to be. Whether we find solutions via religious tolerance, transparency between communities or a sincere debate on Shannon airport, an effort must be made to sterilise any breeding ground that could create a second Kelly. One has done damage enough.