Why the turbo-charged US dollar is causing headaches around the world

The US dollar is trading strongly but its recent success is not good news for some. Sky’s business presenter Ian King takes a look at why.

Thursday 28 April 2022 15:42, UK

These are heady times for the US dollar.

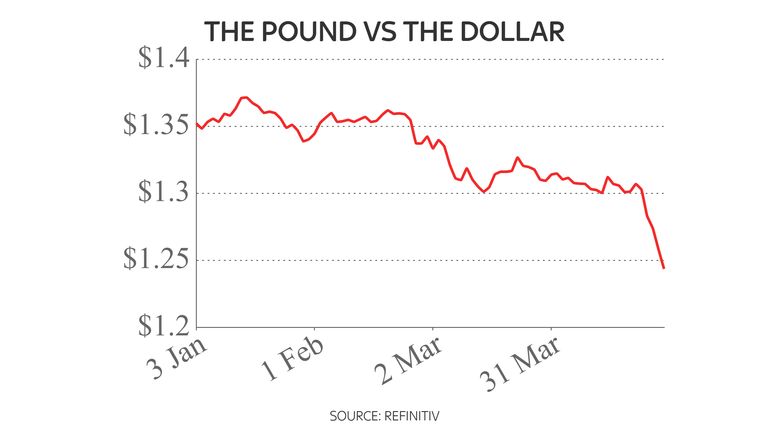

The de facto global reserve currency is currently trading at a two-decade high against the Japanese yen, a five-year high against the euro, and at its highest level against the pound since September 2020.

On the broader measure, the dollar index – which measures how the greenback is trading against a basket of international currencies comprised of the euro, the yen, the pound, the Canadian dollar, the Swedish krona and the Swiss franc – punched to a fresh five-year high today and on the current trajectory may soon hit its highest level for 20 years.

There are several reasons for the dollar’s recent turbo-charged performance.

The first and most obvious is that the outlook for US interest rates has changed considerably in recent days. Jay Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, indicated very clearly last week that the US central bank is likely to raise its policy rate from the current 0.25%-0.5% range to 0.75%-1% at its rate-setting meeting next week.

Then there are the circumstances of the individual currencies against which the dollar moves.

The currency against which the dollar most frequently trades is the euro. The single currency is under pressure against the greenback because, following Russia’s decision to cut gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, investors are beginning to get concerned about the prospect of Italy and Germany being next. A Russian gas ban on Germany, in particular, would tip the Eurozone’s largest economy into a recession that would also drag down others in the bloc.

Bank of Japan continues with ultra-loose monetary policy

Then there is the yen. This has also weakened today against the dollar after the Bank of Japan reiterated its determination to continue with ultra-loose monetary policy. The BoJ said it would keep its main policy rate – which has been at a record low of -0.1% since January 2016 – at “present or lower rates” for now and will continue with its asset purchases, or quantitative easing in the jargon, to keep the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds at no more than 0.25%. The statement was described by Lee Hardman, a foreign exchange analyst at Japanese-owned bank MUFG in London, as “an all-clear to continue selling the yen”.

The pound is the next most heavily-traded currency against the dollar. Sterling has also hit the skids against the greenback during the last week, largely due to Mr Powell’s comments, tumbling from $1.3066 to $1.2436 in that period. It reflects not only growing demand for the dollar but growing uncertainty about the strength of the UK economy in the face of the burgeoning cost of living crisis.

Next up, the Australian dollar. It has also fallen sharply against the greenback of late, declining by nearly 8% during the last three weeks, although this has only taken it back to the level at which it traded in early February. Somewhat weaker has been the New Zealand dollar, down by 1.25% today against the greenback and down by 8% over the last three weeks, despite an unexpectedly big interest rate rise (from 1% to 1.5%) from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand two weeks ago. Both the Aussie and the Kiwi have been hit by concerns over a likely economic slowdown in China, a big export market for the pair, because of COVID-19 restrictions across much of the country.

Swiss franc not quite the safe haven it was

Even the Swiss franc, a traditional safe haven, has fallen against the greenback. It is currently on course for its biggest monthly fall against the dollar in a decade. Some currency analysts argue that, given its close trading relationships with the rest of Europe and its proximity to Russia, the Swissie is not quite the safe haven it was.

A strong dollar has all kinds of implications for the world. It will not be particularly welcomed by US exporters, particularly at a time when weakening growth in the global economy potentially means lower demand for their products and services, with for example Microsoft revealing on Wednesday this week that the stronger dollar clipped around $300m from its sales during the first three months of the year. PepsiCo is another big US corporate that has this week complained about the strong dollar. Expect to hear more complaints of this if, as some currency analysts now expect, the greenback hits parity against the euro – something that was last seen back in December 2002.

The Fed, however, may welcome the downward pressure a stronger dollar exerts on US inflation. That may give the Fed some flexibility and save it from raising interest rates as high as it otherwise might have.

For other countries around the world, a strong dollar presents additional headaches, for example the fact that it makes dollar-priced commodities – most obviously crude oil but also industrial metals like copper and aluminium – more expensive to buy in currencies such as the euro, yen or pound.

Bad news for emerging economies

A stronger dollar is also, in general, bad news for emerging economies when those countries have denominated much of their debt in dollars because it raises their debt servicing costs. Higher US interest rates are also themselves a headache for emerging markets because they tend to draw capital out of those economies and towards the US. In this regard, the key currencies to watch are those of the so-called ‘fragile five’ – Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey – which are particularly reliant on a stable US economy.

Today’s news that the US economy contracted at an annualised rate of 1.4% during the first three months of the year, its first such contraction since the April-June quarter in 2020, may take some of the heat out of the dollar.

But the US economy is still very strong and the figures today reflect, as much as anything, merely a slowdown from the very strong pace of growth posted during the final three months of 2021.

And with the eurozone at risk of recession, the UK facing a slowdown and the Bank of Japan seemingly determined to run ultra-loose monetary policy, the dollar may not be ready to come back down to earth just yet.