How Lithuania is freeing itself from Russian energy

A new pipeline is connecting the Baltic states with Poland, ergo with the entire European gas network. For Poland, it’s been a lifesaver. For Lithuania, it’s just one part of a much larger scheme.

In a field near the Lithuanian village of Jauniunai, the yellow pipeline pops up behind a fence for just a few meters before diving back down underground. Otherwise, there is little to be seen of the 500-kilometer (311-mile) gas pipeline, which begins here and was recently completed to connect Lithuania and Poland.

More important than the few yellow pipes under a blue sky are the three compressor units on a factory site. They provide the necessary pressure to force the natural gas through the pipe over the Polish border.

The “Gas Interconnection Poland-Lithuania” (GIPL) is part of a larger plan to further integrate Lithuania and two other Baltic states, Latvia and Estonia, into the European Union’s energy markets.

The Baltics used to be considered an “energy island” within the EU, said Romas Svedas, a former EU diplomat and Lithuania’s deputy energy minister, now an independent consultant with a teaching position at Vilnius University.

“The significance is connecting the three Baltic states into the energy system and pipeline network of continental Europe,” he told DW.

The Baltics were an ‘energy island’ before the GIPL pipeline connected them to the European energy grid

The Baltics were an ‘energy island’ before the GIPL pipeline connected them to the European energy grid

Not a moment too soon

The completed pipeline couldn’t have come at a better time, especially for Poland.

What’s the mission of the GIPL pipeline? Instead of transporting the fuel from the extraction site to the consumer, like the entire Russian pipeline network does, it wants to enable energy trading and the exchange of resources between buyers. The market decides in which direction the gas is currently headed.

Gas has been flowing through the GIPL pipeline in the direction of Poland since it went live at the beginning of May, after Russia halted gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria overnight at the end of April.

“The pipeline connects the Baltics with the rest of Europe,” the president of the Lithuanian Confederation of Renewable Resources, Martynas Nagevicius, told DW. “That means it also connects Europe’s problems with the Baltics.”

With prices in western Europe rising at record pace as the region moves away from Russian gas, he anticipates further price increases in the Baltics, too.

When construction began in 2015, it’s unlikely anyone thought the pipe would be so urgently needed by the time it was completed. Now, at a ceremony to mark the launch, Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, thanked everyone who contributed to a punctual completion “at a time when we really need the gas supplies.” Lithuanian President Gitanas Nauseda spoke of “energy blackmail from the East.”

“Russia’s war against Ukraine has confirmed our long experience: Russia was and is not a reliable partner,” he said.

The Baltic path to energy independence

The Baltic states, on the other hand, solemnly announced on April 1 that they had already made themselves completely independent of Russian gas supplies. Now they mainly burn gas from the US and Norway. It is delivered via a liquefied natural gas terminal in Klaipeda, Lithuania, with capacity to cover essentially the entire demand of the Baltic states. In addition, there are large underground gas storage facilities in Latvia, a pipeline connection to Finland in the north and now the new pipe in the south towards Poland.

According to the operating company, Lithuania’s only oil refinery also hasn’t touched Russian supplies since April. Lithuania has been pushing for an oil embargo, which the EU is now seriously considering, for some time.

In the Baltics, the issue of energy is inseparable from security policy: “We have a difficult history and difficult relations with our eastern neighbors,” says Nagevicius. “Maybe we Lithuanians have always been a bit suspicious of Russia and Belarus. That’s probably one reason why Lithuania has invested in energy security projects.”

When Lithuania became the first constituent republic to break away from the Soviet Union in 1990 and unilaterally declared independence, Moscow stopped oil supplies. Gasoline was rationed and production had to be halted at some factories. The embargo ended after three months when Lithuania agreed to political negotiations about its own future. Lithuania has always been skeptical of western European energy projects with Russia, especially the two Nord Stream pipelines to Germany.

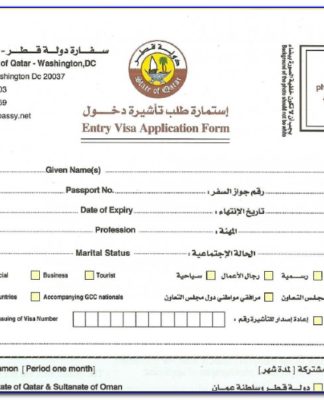

End the monopoly, reduce consumption

The Baltic states’ decision to freeze gas imports in the wake of Russia’s attack on Ukraine was therefore not an impulsive one, but rather the result of years of preparation. In 2014, Lithuania became the first Baltic country to break away from the vertical monopoly of Russian gas giant Gazprom, which traditionally charged higher prices in the Baltics than, for example, in Germany. Energy consultant Romas Svedas recalls how he presented the associated legislative package to parliament at the time.

“It was a very painful process to get the votes for it, while Lithuania, as an EU and NATO member, had to fear difficulties.” Lithuania’s example was followed by Estonia in 2015 and Latvia in 2017.

Reducing consumption also played an important role in phasing out Russian gas. In Lithuania, every second household is connected to the district heating network. For a long time, central burners were heated almost exclusively with Russian gas. By 2020, however, this accounted for only 17%, compared with 80% from biomass, according to the Lithuanian District Heating Association.

Lithuania has spent years weaning itself off Russian gas, after Moscow halted supplies when the country declared independence

Lithuania has spent years weaning itself off Russian gas, after Moscow halted supplies when the country declared independence

Next up: Electricity

From Nagevicius’ point of view, electricity is now the biggest weakness. In the course of its accession to the EU in 2004, Lithuania took its Ignalina nuclear power plant off the grid within five years. The reactor was similar to the one in Chernobyl. But the shutdown plunged Lithuania into great dependence on electricity imports. To this day, two-thirds of its needs are supplied from abroad. The government is now pursuing the expansion of wind and solar power. The plan is to increase them from around 25% of Lithuania’s electricity mix today to 93% by 2035.

More than 30 years after regaining independence, the three Baltic states are also still connected to Russia’s power grid, not western Europe’s. “The system is not secure, because we depend on system services that they perform for us,” said Nagevicius. “The frequency depends on Russia.”

Preparations to connect the Baltic states to the European grid have been underway for years, and some interconnectors have already been laid. Lithuania is now pushing Brussels to revise the timetable and complete the switch before 2025.

At the pipeline opening, President Nauseda suggested the first quarter of 2024. “If the political will is there, projects can be completed “faster than planned.”

This article was first published in German.