20TH CCP CONGRESS

All Xi’s men: Takeaways from China’s historic Communist Party Congress

Issued on: 23/10/2022 – 18:01

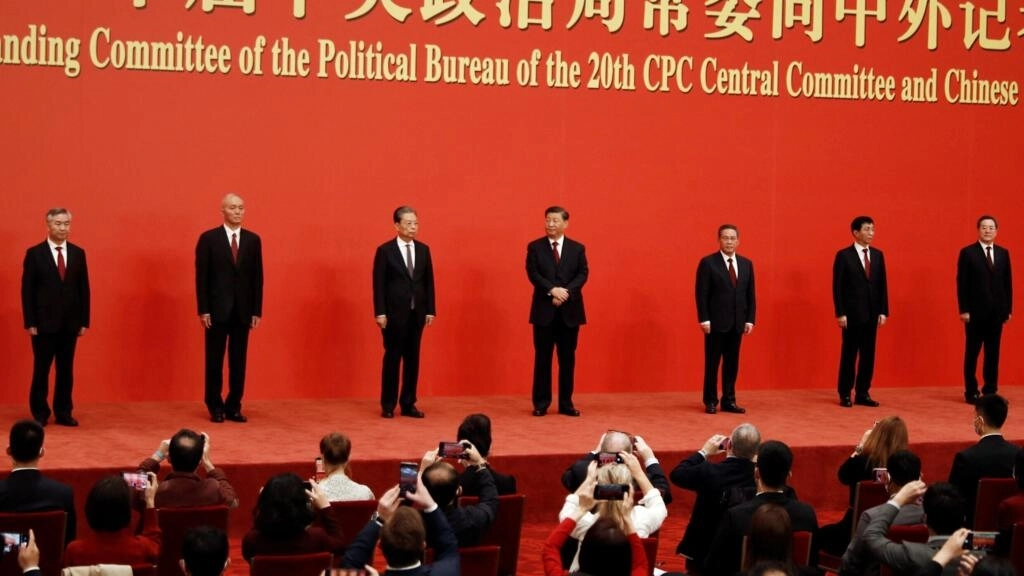

Members of China’s new Politburo Standing Committee take the stage at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China October 23, 2022.

Members of China’s new Politburo Standing Committee take the stage at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China October 23, 2022. © Tingshu Wang, Reuters

Text by:

Leela JACINTO

Follow

7 min

The 20th session of the Chinese Communist Party Congress in Beijing ended Sunday with Xi Jinping securing an unprecedented third presidential term. That was the set piece, arranged for maximum political ends. The real story though was the unscripted dramas – the men who rose and fell in the party’s pecking order – and what that spells for the Asian giant’s future.

For those who thought the twice-a-decade Chinese Communist Party (CCP) National Congress was just boring political theatre, the 20th session, which ended on Sunday, packed in enough drama to prove them wrong.

True, the headline news from the congress was predictable: four years after scrapping the two-term presidential term limit, Xi Jinping did indeed secure his historic third term. The new, seven-member Politburo Standing Committee also featured all men, all wearing identical suits and expressions on stage.

China’s seven-member Standing Committee includes Xi Jinping, Li Qiang, Zhao Leji, Wang Huning, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang and Li Xi.

China’s seven-member Standing Committee includes Xi Jinping, Li Qiang, Zhao Leji, Wang Huning, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang and Li Xi. © Tingshu Wang, Reuters

In China, the party’s Politburo selects the all-powerful Standing Committee. But the new 24-member Politburo also featured no women. Following the retirement of Sun Chunlan, also known as China’s “Iron Lady”, many experts had predicted that the party’s executive body was likely to be an all-male team. They got that right. For all its stated commitment to gender equality, the 20th congress proved that China’s Communist Party has done little to provide women with the managerial and leadership experience required for a Politburo post.

Who did what to Hu?

But this year’s congress also featured a stunning piece of live drama that saw seasoned China watchers scanning video clips and image stills to figure out exactly what happened, and its likely import.

On Saturday, China’s former top leader, Hu Jintao, was unexpectedly led out of the session while he was seated in a prominent position, at the front table in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, right next to his successor, Xi.

The rare break from a tightly choreographed political show came just as journalists were led into the Great Hall of the People, grabbing instant social media attention. It was by no means a clean exit. The frail, 79-year-old former leader appeared unwilling or unable to leave the stage as news cameras flashed and journalists speculated on Twitter. “Highly unusual, Hu didn’t seem to want to leave,” noted Danson Cheng, Beijing-based correspondent for The Straits Times, in a Twitter thread.

Chinese state media immediately said Hu was escorted out to due ill health, but this failed to quell speculation.

“It doesn’t matter if Hu is really sick,” noted Henry Gao from the Singapore Management University on Twitter. “The most important fact about the episode is that this was allowed to take place in full view of all Party delegates and the international media.”

The official Chinese version of the event was entirely credible. Hu has been in frail health in recent years and has rarely been seen in public since he stepped down from the presidency in 2013.

But the sheer difference in China between the Hu presidency years and the current Xi era lent additional weight to Saturday’s sudden high-profile exit. “No matter what the cause, this scene was humiliating, and the image of Hu Jintao being led out is a perfect symbol of Xi’s absolute decimation of the ‘Communist Youth League’ faction,” noted Bill Bishop in his China newsletter, Sinocism.

Factions give way to loyalty to one man

Factionalism – or the balancing of power and positions between competing factions – has been the hallmark of Chinese politics since the Asian giant entered its reform era under Deng Xiaoping.

Hu – who has a background in the Communist Youth League – had a more consultative leadership style during his 2003-2013 rein, which saw relative freedoms in Chinese society as he balanced factions in top leadership posts.

But Hu has fallen from party grace in recent years, with Xi’s barbed denunciations of “the cult of money” and “the search for pleasure” that enabled corruption in the party echelons. Xi’s subsequent anti-corruption drives also enabled the Chinese leader to purge rivals from competing factions.

But the biggest takeaway from the congress for most experts was Xi’s decimation of factions. Referring to the Chinese political system, FRANCE 24’s chief foreign editor Rob Parsons explained that, “in the past, to an extent at least, it allowed for a certain amount of collective government. Now it’s full of people who are absolutely loyal to Xi”.

This includes the man who was selected to replace Li Keqiang, an economist and now outgoing Chinese premier.

Replacing a reformist Li with a loyalist Li

In the lead-up to the 20th congress, all eyes were on Li Keqiang, China’s No. 2 leader and an advocate of market-style reform and private enterprise. If Xi doesn’t succeed in getting Li “replaced with a loyalist”, it’s a “sign that he hasn’t managed to shake up the status quo in his favour”, Alex Payette, a sinologist and director of the Montreal-based geopolitical consultancy Cercius Group, told FRANCE 24 days before the congress started.

In the end, China’s president not only managed to replace Li Keqiang as China’s No. 2, he did it with a loyalist that sent a breathtaking signal of Xi’s consolidation of power.

The chosen man, Li Qiang – who is on track to replace Li Keqiang in March when he finishes his term – is the Shanghai party boss who oversaw the city’s harsh lockdown earlier this year.

While Li Qiang has plenty of administrative experience, the 63-year-old Shanghai bureaucrat does not have experience at the central government level as a vice premier. What’s more, his chances of getting such a high-ranking role were deemed to be low following the controversial “Zero Covid” strategy lockdown in China’s financial hub, when the city’s 25 million residents struggled to access food and basic medical care.

His appointment was seen as the ultimate sign that in Chinese politics today, loyalty can trump merit.

The “biggest news today is that Li Qiang to become Premier”, noted BBC China correspondent Stephen McDonell on Twitter. “The person who stuffed up the Shanghai lockdown, couldn’t properly feed 10s of millions of people, is now in charge of the country’s economy.”

Yes-men provide the information Xi wants

The rise of some men’s political fortunes invariably comes with the fall of others.

In addition to Li Keqiang, the other biggest loser was Wang Yang, the 67-year-old top advisory body head who was once considered the top contender for China’s premiership.

The duo’s political demise was noted with Kremlinology levels of interest by some China analysts. “They look ready to go,” noted Bishop in a tweet that included a shot of Li Keqiang and Wang Yang sitting dourly next to each other in the Great Hall of the People.

The absence of the two men in China’s halls of power was a sign that representatives of rival factions were no longer welcome under the new brand of extreme one-man rule.

Among the new seven-member Standing Committee, all but Guangdong party chief Li Xi worked under Xi in the 2000s, either in the affluent Zhejiang province or in Shanghai.

Daily newsletter

Receive essential international news every morning

Subscribe

“The Standing Committee is very much one-plus-six, and the six other members are clearly yes-men, people who have worked with Xi in the past, people who have pledged clear allegiance to Xi Jinping in the last few years. So there’s no checks and balances anymore in the Standing Committee and in the Politburo itself,” said Jean-Pierre Cabestan, senior research fellow at the Hong Kong Baptist University, and author of “China Tomorrow: Democracy or Dictatorship”.

03:11

The absence of checks and balances may see Xi in a position of one-man power, the likes of which China has not seen since Mao Zedong’s death.

But that also raises the spectre of how effectively the leadership of the Asian giant can tackle the country’s problems. Economic growth in China has fallen over the past few years, fueled by the pandemic, harsh lockdown measures and a global downturn. On the international stage, the war in Ukraine has exposed Beijing’s weak hand in selecting Moscow as an ally.

The question then, is whether the cliques and coteries around Xi can provide solutions for the future. If the past is anything to go by, personality cult rule has never served the country’s interests.

“Almost inevitably, given the fact that these are yes-men who have been put in position, they will want Xi to get the information that Xi wants to get,” noted Parsons. “Personalised power is a problem by itself because Xi will not get the sort of information he needs to tackle the country’s problems.”

.

. © France Médias Monde Infographics