![At diphtheria clinic, medics struggle to treat Rohingya At least 38 people have died since the disease first broke out in the camps three months ago [Ashish Malhotra/Al Jazeera]](http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2018/2/15/4c2c251ddf9349d6a3aac6c070a480f3_18.jpg)

Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh – As she sits by her son Mohammad Farooq’s bedside at a clinic near Bangladesh’s Kutupalong refugee camp, Noor Begum is feeling far more optimistic than she was 24 hours earlier.

“He had a fever and he was vomiting. He could not eat because of the pain,” said Noor, who fled her village of Ludang Para in Buthidaung, Myanmar for Bangladesh as part of the Rohingya exodus that began in late August.

Mohammad is suffering from diphtheria – a serious bacterial infection with common symptoms such as high fever, a sore throat, difficulties in swallowing and a swelling of the neck.

“I couldn’t breathe. My head was paining … my body was shaking,” Mohammad said lying on the bed at the clinic run by the Doctors Without Borders (MSF) aid group.

Until recently, diphtheria had been all but eradicated in Bangladesh but in November, the disease broke out in some of the country’s refugee camps, where many from Noor’s Rohingya community have arrived fleeing a brutal military crackdown in Myanmar.

Nearly a million Rohingya now live in the sprawling refugee settlements in Cox’s Bazar near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border.

It is a densely populated site where sanitation and hygiene are often poor.

Such conditions can create a breeding ground for diphtheria, which is contagious and generally spread among people through airborne droplets passed on from sneezes, coughs or even just talking.

Disease outbreak

At the clinic, Mohammad was given an antitoxin – a powerful drug that blocks the production of toxins produced by diphtheria bacteria – to fight the disease the day before.

“He is now better and I’m so grateful to the doctors,” Noor said looking at her son who looked weak, as he lay covered by a grey blanket. “They’ve taken great care of us and we are so happy.”

But not everyone has been so lucky. At least 38 people have died since the disease first broke out in the camps three months ago.

It’s quite an unknown epidemic because we are not used to having diphtheria anymore

CHIARA BURZIO, MSF HEALTH WORKER

Of the almost 4,500 treated for the disease by MSF during the period, just over 400 have been given the antitoxin that Mohammad received. This is because the drug is limited in supply, not just in Bangladesh but globally, said MSF officials.

Doctors say the antitoxin is reserved for the most severe cases found in the camps. Such patients still need to take antibiotics in addition to the antitoxin. Those with milder cases are only given antibiotics at the largest diphtheria specific centre near the refugee camps.

“Unfortunately the criteria needs to be a little bit strict because we need to be able to give it to the really severe cases,” Chiara Burzio, a nurse and the medical officer in charge of the diphtheria centre, told Al Jazeera.

“We could not give it to all the 4,000 plus [people who have been treated] of course.”

When diphtheria first began spreading among the Rohingya in Bangladesh, supply of the antitoxin was especially limited, meaning Burzio and others had to make an even tougher call – reserving its use only for those under the age of five.

The available supply of the potentially life-saving drug in Bangladesh has since increased, a development that’s been welcomed by doctors on the ground.

But the antitoxin can also come with serious side effects – such as a serious allergic reaction known as an anaphylaxis – further complicating the decisions for doctors about when to administer it, and to whom.

“You can have [an allergic reaction very quickly] … if it’s a big enough anaphylaxis, you can die in a few minutes,” Burzio, 36, told Al Jazeera.

Rohingya denied vaccine in Myanmar

For Burzio and other medical professionals in Cox’s Bazar, fighting diphtheria has required some on the job learning because of how rare the disease has become, particularly in the West.

Outside of Bangladesh’s Rohingya camps, there have recently been significant outbreaks of the disease in Yemen and Venezuela.

“It’s quite an unknown epidemic because we are not used to having diphtheria anymore. So it’s a new thing,” said Burzio, who has previously worked in Liberia and Guinea during the Ebola crisis and war-torn Syria as part of MSF missions.

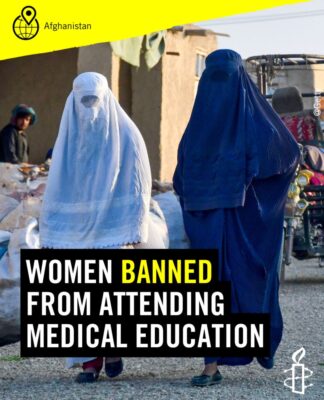

Vaccination has been a key factor in the overall reduction of diphtheria worldwide in recent decades. The outbreak in Cox’s Bazar has therefore led medical professionals to believe that the Rohingya did not receive such preventive care in Myanmar.

Experts say this isn’t surprising, and fits into a broader pattern of exclusion the Rohingya faced in their home country.

“Rohingya have for years been denied their basic rights, and restrictions on their freedom of movement in particular have made it very difficult to access the things most of us take for granted, like health centres and hospitals,” Laura Haigh, a Myanmar researcher for Amnesty International told Al Jazeera.

Rohingya, who are mostly based in the western Rakhine state, have been denied citizenship and have faced widespread discrimination despite living in Myanmar for generations.

Bangladesh’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has launched a vaccination campaign against diphtheria, targeting more than 300,000 Rohingya children between the ages of six weeks and 15 years.

Hope for the future

Twenty metres away from Mohammad’s bed, another Rohingya boy, Ilyas, lies asleep in another shelter in the clinic. One arm stretched across his bed, the other bent near his masked face, the 11-year-old is waiting to receive the antitoxin from the doctors on hand.

Doctors usually seek consent for the procedure from parents before moving forward, but Ilyas is an orphan, which means humanitarian workers are scrambling to track down a relative or community leader to get their permission instead. Given the severity of his diphtheria, it’s a race against time.

But tracking people down in Balukhali-Kutupalong isn’t easy. Ilyas himself has already been referred to a diphtheria centre from another MSF clinic in the area where he initially went for treatment. He is disoriented and can’t effectively explain to aid workers where in the camp he lives.

Eventually, with the help of another humanitarian organisation, consent is obtained and doctors can move forward with the procedure. They hope the antitoxin will have the same effect it had on Noor’s son Mohammad the day before. If it does, and Noor’s response is anything to go by, Ilyas will soon have a new lease on life.

“We are treated here with fatherly care … we are so happy and so grateful and we will pray for all [the doctors],” Noor said with her eyes on her son recovering at the MSF clinic.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS