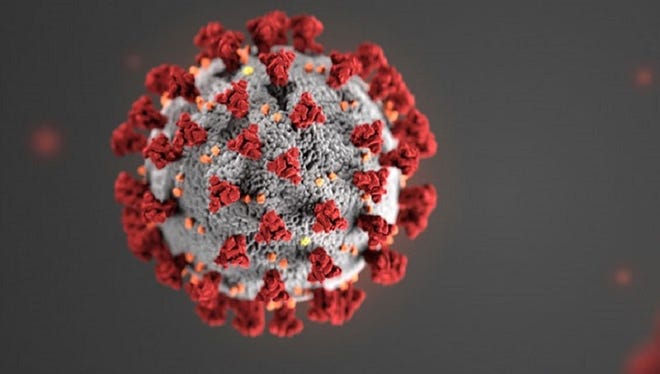

At the United Nations, the world’s longest Zoom meeting is underway as presidents and prime ministers meet virtually amidst a pandemic that has killed almost a million people, an economic depression with no modern parallel, and a tide of polarization and division that threatens the social fabric in many countries.

This week also marked the 75th anniversary of the United Nations, a platform for global cooperation that was born from the destruction of the wars of the first half of the 20th century. The UN has — so far, at least — fulfilled its promise to save succeeding generations from a third global war.

Despite its many accomplishments, the United Nations has been criticized for being less effective and efficient than it could be. Now it faces a wave of new challenges as the global systems on which all of us rely threaten to unravel and governments seem often unwilling to work together to confront shared threats.

In the run up to the 75th anniversary, António Guterres, the UN’s Secretary-General, launched a global conversation in which he asked people from across the world to share their hopes and fears for the future, and to propose solutions for the planet’s most pressing challenges. Over a million people from 193 countries took part making it one of the largest consultations of its kind.

Earlier this week, at the opening of the General Assembly, President Trump accepted that the world is again engaged in a global struggle, but he may be surprised by people’s hunger for a global approach to resolve this conflict. The average global citizen may be fearful for her future, but she knows that responding to those fears requires more global cooperation, not less.

The international consensus for global cooperation is overwhelming. Almost nine in 10 respondents to the United Nations survey believe that international collaboration is vital to tackle contemporary challenges. Despite the grumbling of some diplomats, the UN is also immensely popular. Roughly three quarters of all respondents believe that the United Nations should lead the charge.

But people also know that multilateralism must change and adapt. The world has changed — including with the rise of powers like China and India, the relentless expansion of digitization and persistent in-country inequality. The UN has work to do to connect its efforts more directly to people’s lives. Over half of us feel that the UN is too remote. Many are not entirely sure what the organization does.

The UN Charter begins with the words “We the Peoples,” but at a time when many people feel alienated from institutions, global platforms can seem distant and out-of-touch. This is seized on populists and conspiracy theorists who cynically undermine truth and create division. The UN must strengthen the “we” in the peoples, actively building the trust that helps us work for a shared future.

People also want the UN to look and sound more like them. They want more representation for women, a greater say for indigenous voices and minorities, and active leadership from the private sector and from mayors. Young people are the biggest supporter of collective action and cities are where most people live, so it is hardly surprising that they are demanding space in the international system to shape a more resilient and sustainable future.

In the short term, virtually all those who took part in the global conversation want the UN to focus its energies and resources on tackling the pandemic and the vulnerabilities it has exposed. They want a more equal world, with better access to health care, education, water, sanitation and other basic services.

They also feel that greater solidarity and shared support should be directed toward those places hardest hit by the pandemic. They know that the pandemic will fester if only more privileged countries and communities have access to the resources that are needed to respond, recover and rebuild.

In the longer-term, climate change is people’s overwhelming priority for action by the UN. There is widespread anxiety about the impacts of climate change, and deep worries that environmental conditions are set to worsen in the coming years. These findings are echoed in countless scientific studies, as well as the surge of warming temperatures, forest fires, melting glaciers and breathtaking decline in biodiversity.

As ever, the problem is not a lack of ideas, but the political will to take them forward. The secretary-general is keen to turn these aspirations into a set of concrete proposals for action, a “common agenda” to help “reset” the world in the COVID-19 era. This will require building a model for multilateralism that is more inclusive and more effective.

Many of the media headlines from this year’s General Assembly will speak of tension between the world’s most powerful countries, especially China and the U.S. Some will claim that widening these geopolitical divisions and fueling culture wars is a smart way to win political battles at home. We do not believe this to be true.

Across the world, people share common hopes and fears about the future. They have a genuine commitment to the values of the United Nations. And they want governments to use the UN as a platform for action to secure peace, prosperity and sustainability — the battle between cooperation and division is the real ‘global struggle’ we face, and it’s one we must urgently win.

Ilona Szabo is the Executive Director of the Igarape Institute. Elizabeth Cousens is the president and CEO of the United Nations Foundation. Robert Muggah is co-founder of the Igarape Institute.

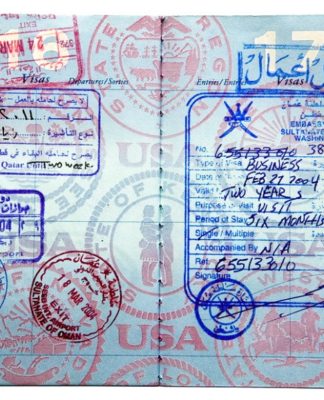

![How to get a Qatar Family Residence Visa? [ Updated ]2022](https://welcomeqatar.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/maxresdefault-2-324x400.jpg)