Back to homepage / Europe

FALL FROM GRACE

How Russian state media is tearing down Prigozhin’s reputation as a ‘man of the people’

The public broadcast of police raids on Wagner Group head Yevgeny Prigozhin’s home and office are an obvious attack on the mercenary’s cherished reputation as a straight-talking patriot fighting against corruption – and, experts say, a warning to anyone else who might challenge President Vladimir Putin’s rule.

Issued on: 07/07/2023 – 16:31

7 min

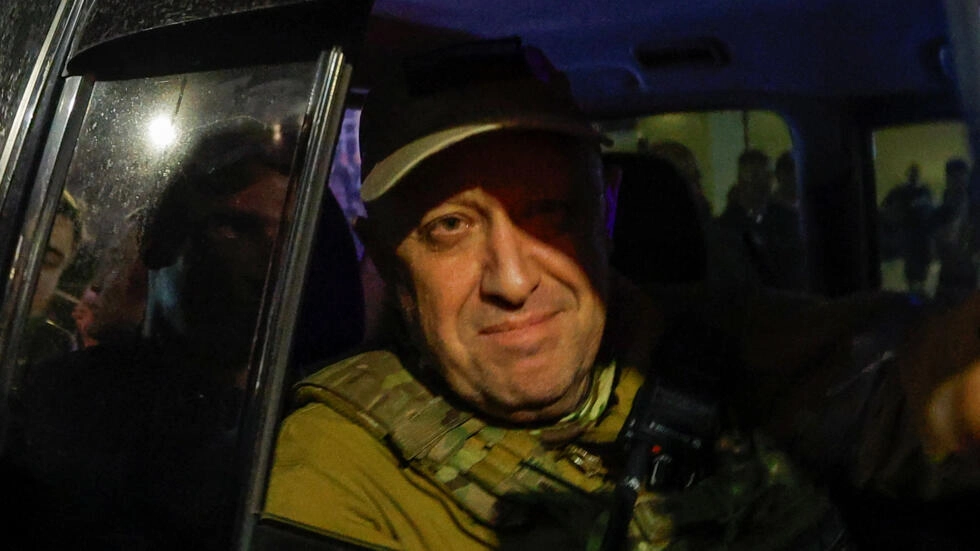

This video grab taken from a handout footage posted on May 5, 2023 on the Telegram account of the press-service of Concord — a company linked to the chief of Russian mercenary group Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin — shows Yevgeny Prigozhin addressing the Russian army’s top brass.

This video grab taken from a handout footage posted on May 5, 2023 on the Telegram account of the press-service of Concord — a company linked to the chief of Russian mercenary group Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin — shows Yevgeny Prigozhin addressing the Russian army’s top brass. © Handout / Telegram/ @concordgroup_official / AFP

Text by:

Paul MILLAR

As humilations go, they don’t come much more public.

On Wednesday night, state-owned broadcaster Rossiya-1 broadcast what it described as exclusive footage of raids launched on Yevgeny Prigozhin’s St Petersburg residence and office the night after the head of the mercenary Wagner Group called off his march on Moscow.

It was a rare look into the lavish lifestyle that only years of running an international mercenary force can buy. Among the obligatory grand piano, indoor swimming pool, jacuzzi and sauna, the footage showed more explicit mementos of almost a decade spent building a private militia with the full backing of the Russian state: an arsenal of automatic weapons, crates of gold bullion, a sheaf of false passports and, in one closet, shelf after shelf of unconvincing wigs.

Other, grislier souvenirs may have had more sentimental value: a commemorative sledge-hammer – Prigozhin’s apparent weapon of choice for bludgeoning to death those he accused of being traitors – and a censored photograph purportedly showing severed heads left lying on some unknown road. On the walls, rows of squinting saints peered down at the passing police in mute disapproval.

Journalist Eduard Petrov, who was invited on the programme to present the footage, said that police had found 600 million roubles ($6.58 million) worth of cash in Prigozhin’s properties. For a man who consistently called out corruption in Russia’s military command, he said, it was a shocking sight.

“I consider that the creation of Yevgeny Prigozhin’s image as a people’s hero was all done by media fed by Yevgeny Prigozhin,” said Petrov. “After it failed, they quickly closed and fled.”

In the crosshairs

Now, that same media machine that helped set Prigozhin’s myth in motion seems to have ground to a halt. Prigozhin’s media holdings group Patriot Media, whose flagship outlet, the RIA FAN news site, had faithfully praised Prigozhin and his Wagner Group while maintaining the Kremlin’s hard-line nationalist rhetoric throughout the fighting in Ukraine, shut down without explanation the week after the failed uprising.

A week later, Russian media reported that communications watchdog Roskomnadzor had blocked RIA FAN’s website, along with those of Politics Today, Economy Today, Neva News and People’s News, a collection of online media outlets that had consistently published pro-Prigozhin content. St Petersburg-based outlet Rotunda also reported that the Internet Research Agency (IRA), Prigozhin’s infamous troll farm that paid interns a pittance to post pro-Kremlin content on social media, had also closed down.

Even Concord, the catering company that had first earned Prigozhin a seat at the high table – and the nickname “Putin’s chef” along with it – found itself in the Kremlin’s crosshairs. In an address to the Russian people, President Vladimir Putin announced that the company – which he claimed had made 80 billion roubles [roughly $875 million] through plum state contracts to feed the Russian army – would be having its finances investigated.

“I hope nobody stole anything, or didn’t steal much, but we’ll sort this out,” he said.

Read more

What does the future hold for Wagner in Africa after the failed rebellion?

For Stephen Hutchings, professor of Russian studies at the University of Manchester, Wednesday night’s spectacle was part of a wider campaign against the disgraced mercenary.

“Prigozhin’s reputation must be taken down, as he has abused his autonomy and committed what Putin sees as ‘treachery’ – the worst crime of all in his eyes,” he said. “There is now a coordinated media campaign against him. This includes ‘exposés’ of the vast wealth held at Prigozhin’s mansions to undercut his populist ‘man of the people’ image.”

‘You wouldn’t want him near the nuclear trigger’

Jeff Hawn, a specialist in Russian security and non-resident fellow at the US-based New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, said that the broadcast was likely an effort to puncture Prigozhin’s burgeoning cult of personality.

“For the broader Russia public, the message is: This is not your guy, he’s as corrupt as everyone else,” he said. “During the mutiny, Prigozhin’s broader message was against corruption. This is the state saying that the emperor has no clothes.”

By drawing a sharp contrast between his presence on the front line and the generals directing the war from distant bunkers, Prigozhin’s use of broadcast and social media has put a more human face on what Moscow still calls its special military operation in Ukraine.

“Prigozhin had, prior to this, certainly used his media holdings to cultivate his own reputation as a no-nonsense, effective operator with strong patriotic values, but capable of achieving what weak and corrupt state institutions cannot,” Hutchings said. “He has drawn heavily on populist rhetoric, presenting himself as a straight-talking – and foul-mouthed – man of the people.”

It’s a tactic that seems to have served him well. A poll released by the independent Levada Center in the days following the insurrection found that although Prigozhin’s popularity had been cut in half since his attempted uprising, nearly a third of respondents still expressed either total or partial approval of the mercenary. Although he was keen to stress that Prigozhin was a war criminal in his eyes, Hawn was blunt about Prigozhin’s domestic appeal.

“He’s very working class, very crude and straight-talking,” he said. “He’s kind of like your drunken uncle – you wouldn’t want him near the nuclear trigger, but he tells it like it is.”

But the Russian public were not the only ones watching black-clad police burst into Prigozhin’s home. State television is also closely followed by Russia’s political and business elite hoping to glean some sign of the Kremlin’s latest political line. Hutchings said that the message of the public raids was all too obvious to the oligarchs and apparachiks who made up Russia’s elite.

“The message is therefore also intended to send a strong signal to them that they should think twice about acting against Putin and his policies, for fear of suffering similar damage to their security and reputation,” he said. “This is why the dominant Western narrative that the failed coup has seriously weakened Putin is only part of the story. The episode is also being used to Putin’s advantage with emphasis placed on his role as a unifier, on the dangers of chaotic and bloody civil wars, and on the likelihood that coups of this sort are destined to fail.”

Hawn said that footage of cardboard boxes stuffed with stacks of uncounted hundred-dollar bills being loaded into police vans was as naked a threat as Putin’s potential opponents could hope to see.

“What do they fear? The wrath of the state turned against them,” he said. “It’s all performative, to show you cannot kick against the state because the state will kick back, and you’ll lose the one thing you care about – which is the money you’ve made.”

Breaking up Prigozhin’s empire

Finnish Institute of International Affairs’ Senior Research Fellow Margarita Zavadskaya said that Prigozhin’s fall from grace had cut him off from the state contracts upon which the well-connected businessman had built his empire.

“I would expect Prigozhin to be stripped of the majority of his economic assets and, perhaps, access to weapons, ” Zavadskaya said. “Prigozhin’s business heavily depends on state ‘investments’ and public contracts, and is unlikely to survive on its own.”

Read more

Open rebellion against Russia may be Wagner chief Prigozhin’s last stand

In the end, she said, the media machine that Prigozhin had set up had done little to support the mercenary in his moment of crisis.

“The notion of an all-powerful media empire maintained by Prigozhin is more of an image he sought to portray rather than a reflection of its actual capacity and effectiveness,” she said. “Notably, during the mutiny, RIA FAN and other news media outlets remained completely silent, making no attempt to support Prigozhin or his revolt. The majority of Prigozhin’s media empire is comprised of pragmatically driven managers who were primarily focused on generating profits and fulfilling Prigozhin’s demands.”

Daily newsletter

Receive essential international news every morning

Subscribe

It is that same pragmatism that may end up serving Putin’s interests in the years to come. With Prigozhin out of the picture, Hutchings said, much of the mercenary chief’s business empire will likely end up parcelled out among people closer to the president – or even in the hands of state security or military intelligence.

“It is important to point out that state media reports on the total dismantling of Prigozhin’s media empire are not to be taken at face value,” he said. “Whilst he is being removed from involvement with these operations, it is very unlikely that they will be terminated altogether. Much more probable is that the more significant ones among them, including the infamous IRA troll factory in St Petersburg, will be taken over by actors much closer to the Kremlin, including [Russia’s security service] the FSB and/or the [military intelligence agency] GRU.”

As his business empire crumbles around him, though, Prigozhin can take some comfort in the fact that much of his personal wealth will seemingly remain intact – likely as part of the closed-door negotiations between Prigozhin and Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko that brought Wagner forces back from the brink of bloodshed.

The independent Moscow Times reported this week that Russian authorities returned 10 billion roubles ($111.2 million) to the exiled leader that had been seized in police raids during his failed rebellion.

“He’s going to lose his houses and his properties in Russia, he’s just going to be able to keep some of his personal wealth,” said Hawn. “But he’s going to lose his media influence, and Wagner – they’re going to be broken up and redistributed among the Russian elite as a means of securing favour. So he gets to keep his personal assets – but he’s out.”